Understanding Bipolar

Understanding Bipolar Disorder (BD)

Bipolar Disorder (BD), formerly known as Manic-Depressive Illness, is a brain-based disorder characterised by shifts in mood, energy, and functionality. These shifts alternate between periods of low mood or depression and high-energy states known as mania or hypomania.

These mood states are distinct clinical experiences, differing from ordinary feelings of happiness or sadness. They involve uncontrollable and pervasive mood shifts that significantly impact a person’s ability to work and function socially.

Mania

Mania and hypomania are two types of episodes in bipolar disorder, with mania being more severe and causing more noticeable disruptions in work, social activities, and relationships. Mania can also lead to psychosis, necessitating hospitalisation.

Both manic and hypomanic episodes include three or more of these common symptoms (with differences in severity):

- Abnormally upbeat, jumpy, or wired feelings

- Increased goal-directed activity

- Grandiosity

- Elevated energy levels or agitation

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Reduced need for sleep

- Excessive talkativeness (pressured speech)

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Impulsive or risky behaviours such as excessive spending, risky sexual activities, impulsive travel, or increased substance use.

Types of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar Disorder is classified into four distinct types by the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 2013):

- Bipolar I Disorder: Characterised by manic episodes lasting at least 7 days or by severe manic symptoms requiring immediate hospitalisation due to psychosis. Depressive episodes typically last at least 2 weeks, and mixed episodes (combining depression and manic symptoms) are also possible.

- Bipolar II Disorder: Marked by recurrent depressive episodes and milder hypomanic episodes without severe manic symptoms.

- Cyclothymic Disorder (Cyclothymia): Defined by numerous periods of hypomanic symptoms and depressive symptoms lasting at least 2 years. However, the symptoms do not meet the criteria for full hypomanic or depressive episodes.

- Other Specified and Unspecified Bipolar and Related Disorders: Encompasses bipolar symptoms that do not fit into the above categories. This category includes variations within the bipolar spectrum.

Tests for Bipolar Disorder

When it comes to clinical online tests for bipolar disorder, it’s important to note that while some resources are available online, they are generally not substitutes for a formal diagnosis by a qualified healthcare professional. However, they can provide initial screening or self-assessment tools that may prompt individuals to seek professional help if necessary. Here are a few notable options:

- Mood Disorders Questionnaire (MDQ): This is a validated screening tool designed to detect bipolar disorder. It consists of 13 questions about symptoms related to manic and hypomanic episodes. The MDQ can provide a score indicating the likelihood of bipolar disorder and is often used as a first-step screening tool.

- Bipolar Spectrum Diagnostic Scale (BSDS): Developed by Dr. Ronald Pies, this self-report questionnaire helps assess the presence and severity of symptoms associated with bipolar spectrum disorders. It consists of 19 items and is used to screen for both bipolar I and bipolar II disorders.

- Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM): This is a brief, five-item questionnaire designed to assess the presence and severity of manic symptoms. It’s used to screen for manic symptoms and can be helpful in identifying potential bipolar disorder.

- Black Dog Institute Diagnostic Online Test: A few questions and a helpful online resource.

It’s essential to use these tools in conjunction with professional evaluation and not rely on self-administered tests for diagnosis. If you or someone you know is experiencing symptoms that suggest bipolar disorder, it’s crucial to seek evaluation and guidance from a qualified healthcare provider, such as a psychiatrist or psychologist, for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

To book a thorough personal assessment with me today click here.

Women & Bipolar Disorder (BD): Understanding Hormonal Fluctuations and Effects on Mood

Bipolar Disorder (BD) presents differently in females compared to males. Females with BD often exhibit more rapid cycling and mixed features, experience a higher number of depressive episodes, and show a higher prevalence of BD type II.

There is a strong association between BD and the risk of postpartum mood episodes. Many females with BD also experience varying degrees of premenstrual mood worsening; 45 to 68% report premenstrual mood symptoms of varying severity*. Females diagnosed with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) are significantly more likely to have BD, up to 8 times more compared to the general population*.

When BD is comorbid with PMDD, the course of illness tends to be more complex. This includes increased psychiatric comorbidities, earlier onset of BD, and a greater number of mood episodes. Importantly, there appears to be a link between puberty and the onset of BD in females with comorbid PMDD.

Treating BD comorbid with PMDD presents challenges. First-line treatments often involve SSRIs, which can carry a risk of treatment-emergent manic symptoms

Distinguishing Bipolar Disorder (BD) from Unipolar Depression (Major Depressive Disorder) (MDD)

Understanding the Bipolar Spectrum

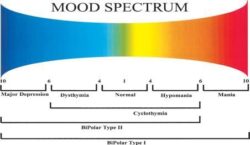

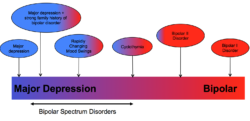

In recent years, clinicians and researchers have adopted a spectrum model for understanding Bipolar Disorder (BD), moving away from the traditional view of BD as solely Bipolar I or II. The spectrum now encompasses a continuum that connects unipolar (Major Depressive Disorder, MDD) and bipolar conditions. This model recognises individuals who may not meet strict diagnostic criteria for BD but still experience symptoms and functional impairment. These individuals often respond better to mood stabilising medications rather than antidepressants.

This spectrum model allows clinicians to better describe and understand their patients’ experiences. Instead of simply asking whether a patient has Bipolar Disorder or not, clinicians now assess where they fall on the spectrum of bipolarity (Phelps, 2016).

For further reading, I highly recommend:

- A Spectrum Approach to Mood Disorders (Norton, 2016)

- Bipolar, Not So Much (Norton, 2016)

- Why Am I Still Depressed? (McGraw-Hill, 2006)

In their 2002 review, Dr. Ghaemi and colleagues characterised Bipolar Spectrum Disorder as exhibiting certain bipolar markers in the absence of identifiable hypomania, summarised by the acronym WHIPLASHED:

- W: Worse or “wired” when taking antidepressants

- H: Hypomania, hyperthymic temperament, or mood swings by history

- I: Irritable, hostile, or mixed features in depression

- P: Psychomotor changes (retardation or agitation)

- L: Loaded family history of affective illness (not necessarily bipolar disorder only)

- A: Abrupt onset or termination of episodes

- S: Seasonal or postpartum pattern of depression

- H: Hyperphagia (overeating) or hypersomnia (oversleeping)

- E: Early age of onset of depression (18-24 years)

- D: Delusions, hallucinations, or other psychotic features

This approach provides a nuanced understanding of mood disorders, emphasising individual variability and response to treatment.

What Bipolar Disorder Isn’t

Bipolar disorder can sometimes be mistaken for or coexist with other conditions:

- Endocrine problems (like hyperthyroidism)

- Neurological issues (such as brain tumours)

- Autoimmune disorders (like lupus)

- Other psychiatric mood disorders (such as borderline personality disorder or schizophrenia)

- Chronic or clinical depression (often misdiagnosed as bipolar)

- Reactions to certain medications

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), especially in children

- Conduct disorder, especially in young children

- Substance abuse

Accurate diagnoses are best made by experts who specialise in bipolar disorder. They can differentiate between anxiety disorders, depressive states, and overlapping symptoms of bipolar disorder. While diagnostic questionnaires effectively identify mood disorders and depression, tests specifically for subtle symptoms like hypomania and Bipolar II are less common.

To reduce misdiagnosis, pioneers in bipolar research developed tools like the HCL-32 (Hypomanic Checklist), which successfully distinguishes major depression from bipolar disorder in 51-81% of cases.

Best Approach to Understanding the Diagnosis

Bipolar disorder isn’t a life sentence. Similar to managing diabetes or high blood pressure, it requires consistent medication and lifestyle adjustments. Long-term medication significantly reduces the impact on daily life. Lifestyle changes support goals like career success, strong relationships, romance, and family life.

Many highly creative and productive individuals have thrived with bipolar disorder. Notable figures in art, literature, business, and politics, including Einstein, Van Gogh, Hemingway, and Newton, have had the disorder.

Maintain a healthy sense of identity and leverage personal strengths to manage treatment effectively. If you’re assertive, sociable, or intellectual, use these qualities to advocate for yourself and learn about your illness.

Remember, your current state isn’t permanent. With proper treatment, you can return to a manageable state similar to your previous functioning. Recovery may require a period of adjustment, akin to recuperating after a severe illness.

Although bipolar disorder is lifelong and sometimes chronic, you can manage mood swings and symptoms with a personalised treatment plan from a knowledgeable psychologist or health professional. Early intervention and accurate diagnosis are crucial for positive outcomes.

Understanding mood disorders and symptoms can be challenging. Many people wait over a decade for a correct diagnosis, with up to 40% initially receiving incorrect diagnoses. Seek help promptly to prevent the progression of this disorder.

Let’s explore more together – schedule a consultation today to gain further insights.

References

Diagnostic criteria sourced from the Mayo Clinic: https://www.mayoclinic.org/

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. http://www.psychiatryonline.org.

Phelps, James (2016) Spectrum Approach to Mood Disorders – Not fully Bipolar But Not Unipolar – Practical Management. W.W. Norton & Company

Ghaemi SN, Ko JY, Goodwin FK. “Cade’s Disease” and beyond: misdiagnosis, antidepressant use, and a proposed definition for bipolar spectrum disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2002 Mar; 47 (2):125-34.